As the South votes to become independent, tens of thousands remain enslaved.

By John Eibner & Charles Jacobs

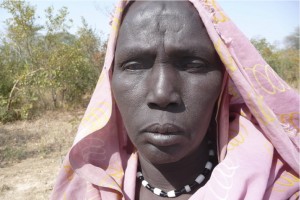

Juba, Sudan/ On Jan. 9, the people of South Sudan began their week-long referendum to decide whether to separate from the Arab-Muslim North and form an independent country. But Achol Yum Deng didn’t vote. Though she has more reasons to seek separation from the North than most of her countrymen, she couldn’t register: Since 1998, Achol was a slave serving her master in the North and was only liberated just before the voting began.

The war booty of a man named Adhaly Osman, Achol was threatened with death, gang-raped, genitally mutilated, forced to convert to Islam, renamed “Mariam,” and racially and religiously insulted. She lost the sight in one eye when her master thrashed her face with a camel whip for failing to perform Islamic rituals correctly. This mother of four saw two of her children beaten to death for minor misdemeanors. She also lost the use of one arm when her master took a machete to it in response to her failure to grind grain properly.

Achol is one of 397 slaves whose liberation was facilitated and documented by Christian Solidarity International and the American Anti-Slavery Group in the state of Northern Bahr el Ghazal as voting commenced.

The British suppressed black slavery in Sudan in the first half of the 20th century. But the practice was rekindled in the 1980s as part of the surge in Islamism in the region. In 1983, when Khartoum’s radical leaders declared strict enforcement of Shariah law throughout the country, the Christian and tribalist South resisted. Shariah-sanctioned slave raids were used as a weapon to break Southern resistance.

Armed by the government in Khartoum, Arab militias would storm African villages, shoot the men, and capture the women and children. The captives were beaten and raped immediately.

Taken North—roped by their hands into lines or carried individually on horseback—they were distributed to masters. Boys were used as goat and cow herders, little girls as domestics. As they grew, they became concubines and sex slaves. Slaves slept with the animals and were given rotten scraps from the masters’ table. Boys were killed for losing a goat.

There is a racist aspect to this slavery. Blacks were cursed as abd (black slave) and kuffar (infidel). Many were forcibly converted to Islam. The North-South war, lasting 23 years, was ultimately declared a “jihad” by Sudan’s Islamist President Omar al-Bashir.

The U.S.-brokered Comprehensive Peace Agreement of 2005 ended the slave raids and confirmed the South’s right to self-determination. But it failed to create a mechanism for the return of slaves. Over 35,000 people, according to representatives of the Committee to Eradicate the Abduction of Women and Children, remain in bondage today.

Cases like Achol’s have been known to the elites in the international community from the early days of Khartoum’s war against the South. But the U.N. and Western governments have been slow to tackle this internationally recognized crime against humanity. It was not until 1999, 16 years into the war, that Unicef, the world largest child welfare organization, finally acknowledged the reality of slavery in Sudan.

But threats made by the government of Sudan against U.N. operations forced Unicef to backtrack. Meanwhile, in 1999, the Arab League declared that slavery was nonexistent in Sudan and that to say otherwise was an insult to Arabs and Muslims. For fear of offending Islam, many Western NGOs have turned a blind eye.

It was the issue of slavery that sparked American interest in Sudan in our time. Reports in the mid-’90s about black slaves shocked ordinary Americans and generated an unlikely coalition that included Rep. Barney Frank (D., Mass.) and Pat Robertson, then Sen. Sam Brownback (R., Kan.), Village Voice columnist Nat Hentoff, and the late Republican Sen. Jesse Helms.

As the reality of Sudan’s partition sinks in, there are now tens of thousands of free South Sudanese returning home from the North. They come in the hope of living freely—and also fearing the angry reaction of Northern Arabs to the South’s decision to separate.

But those who remain enslaved in the North are effectively disenfranchised from participation in the birth of what is likely to be Africa’s newest nation-state. People of goodwill should demand that all of the remaining slaves be set free.

Mr. Eibner is the CEO of Christian Solidarity International-USA. Mr. Jacobs is president of the American Anti-Slavery Group.